Girvan Festival is a great opportunity for an extended stay in South West Scotland. As well as being internationally recognised as a UNESCO Biosphere, the area is steeped in the history and lore of traditional music.

Moniaive Folk Festival

Our friends over the hill run the fantastic Moniaive Folk Festival that falls the weekend after Girvan. Visiting both Festivals in a single trip is surely one of the best ways to experience all that South West Scotland has to offer!

You can use the map below to explore a few of the many possible routes you can take through the South West from Girvan to Moniaive.

Boswell Book Festival at Dumfries House

The week after Moniaive Festival the Boswell Book Festival takes place at Dumfries House, Ayrshire’s stunning 18th-century house and estate with a range of family-friendly attractions.

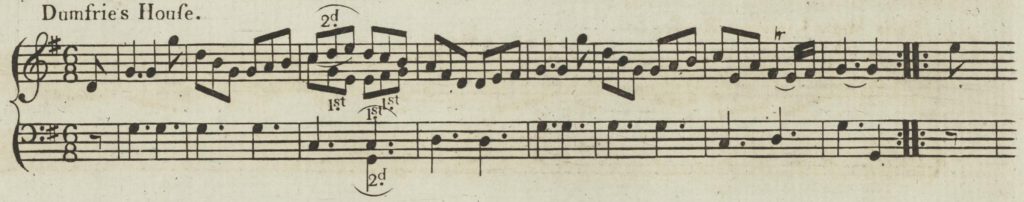

Committed folkies may know the tune Dumfries House. First published in 1782, the tune is still played today by country dance and ceilidh bands and is known in the Irish tradition as The Maho Snaps.

Dumfries House from John Riddell’s “A Collection of Scots Reels Minuets &c.” via hms.scot

Dumfries House from John Riddell’s “A Collection of Scots Reels Minuets &c.” via hms.scotBoat trip to Ailsa Craig

You can’t visit Girvan, or travel along the Ayrshire coast, without seeing the imposing granite island of Ailsa Craig guarding the entrance to the Firth of Clyde.

The island’s name derives from the Gaelic for Fairy Rock or Elizabeth’s Rock. Early texts and the medieval Irish sagas give the island a variety of names including Alasan, Carraig Alasdair and Ealasaid a’ Chuain however you’re much more likely to hear it referred to today simply as Paddy’s Milestone, a nickname that has come from the island sitting at the midpoint of the sea journey from Belfast to Glasgow.

Duncan fleech’d, and Duncan pray’d,

Ha, ha, the wooin o’t!

Meg was deaf as Ailsa Craig,

Ha, ha, the wooin o’t!

from Duncan Gray by Robert Burns

Nowadays the island is an important bird sanctuary and famously the source of granite for all the world’s curling stones!

Trips to or around the island leave from Girvan aboard the MFV Glorious and the Paddle Steamer Waverley (depending on schedule).

Bargany Gardens

Bargany Gardens is one of Scotland’s hidden gems, just over 5 minutes drive from Girvan. The extensive 50 acre mature woodland garden boasts a fine variety of azaleas, rhododendrons, fir trees, a cherry orchard, rock garden, walled garden and ornamental loch.

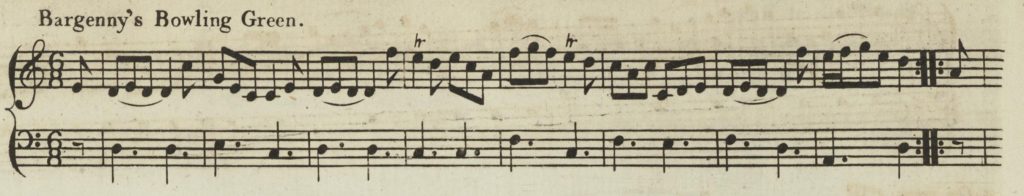

Carrick poet Hew Ainslie (1792–1878) was born at Bargany and immortalised the gardens in his song The Bourocks o Bargany and John Riddell (1718–95), the blind fiddler of Ayr, wrote a number of tunes inspired by the estate including The Woods of Bargenny, Mrs Hamilton of Bargenny’s Reel and Bargenny’s Bowling Green which featured on Capercaillie’s debut record Cascade in 1984.

Bargenny’s Bowling Green from John Riddell’s 1782 collection was recorded by Capercaillie on their debut album

Bargenny’s Bowling Green from John Riddell’s 1782 collection was recorded by Capercaillie on their debut albumThe Gardens open for just one month each year on the 1st May — as luck would have it, the day after Girvan Festival! Entry is an incredibly reasonable £2 (under 16s go free) from the Bargany Estate Facebook page.

Culzean Castle

Just 15 minutes drive north of Girvan, perched above the Carrick Shore is the magnificent, cliff-top Culzean Castle. Once the playground of the Earl of Cassillis, the Castle is now in the care of the National Trust for Scotland and open to the public as Culzean Castle and Country Park. In addition to guided tours of the Castle, attractions include the Home Farm Shop, Second-hand Bookshop, deer park, cafes, adventure playgrounds and extensive woodland, beaches, parkland and cliff walks.

Local tradition has it that the Clan Kennedy of Culzean are the same family immortalised in the famous ballad, The Raggle Taggle Gypsy or The Gypsy Laddie [Child 200, Roud 1]. The story goes that Lady Jane Hamilton, wife of the 6th Earl, eloped with Johnnie Faa, a 17th-century outlaw and her husband pursued them and hanged Faa and his men at nearby Cassillis House.

The ballad and its many variants have been recorded countless times by a vast catalogue of artists including Jeannie Robertson, Planxty, The Waterboys, Jean Redpath, The Tannahill Weavers and Nic Jones.

The Ayrshire-origin tradition goes back to at least the 1770s when the Cassillis name appears in the Mansefield Manuscript — a personal collection of songs kept by an upper-class Edinburgh lady. Robert Burns was the first to put the tradition into print in 1788 when he stated in the 2nd volume of the Scots Musical Museum, “Neighbouring tradition strongly vouches for the truth of this story”.

Burns’s annotation, “tradition strongly vouches for the truth of this story”.

Burns’s annotation, “tradition strongly vouches for the truth of this story”.In fact the tradition is probably much older — the very earliest surviving appearance of the song in print is on a broadside slip produced in Newcastle from at least 50 years earlier than the Musical Museum in which the vengeful husband is called “the Earl of Castle’s” – almost certainly a mishearing, in the midst of oral transmission, of the Cassillis name.

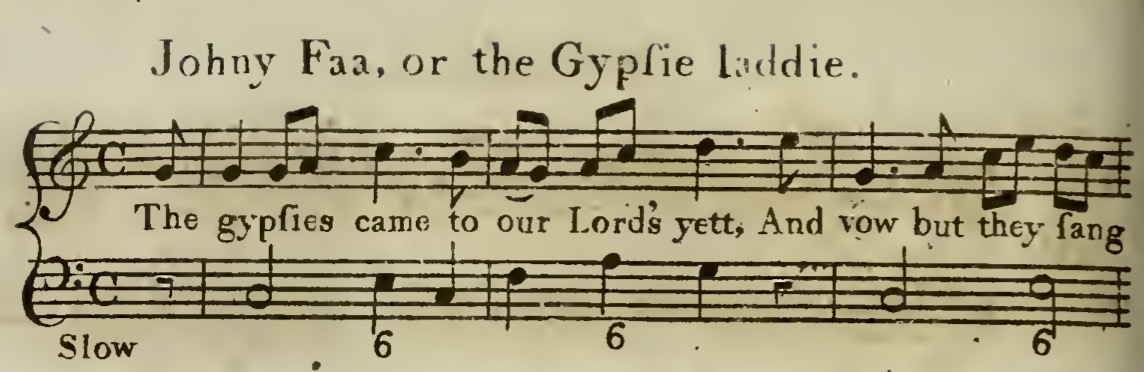

Thy Gypsy Laddie from Robert Burns’s Scots Musical Museum.

Thy Gypsy Laddie from Robert Burns’s Scots Musical Museum.There is also a musical link — the earliest known tune the ballad was sung to (shown above) was known by 1742 as Johnnie Faa but appears under the title Lady Cassilles’ Lilt in a manuscript produced some time prior to 1635. This links the Ayrshire family with the song around a century before the first surviving texts of the song. The origins of the tradition are certainly very old — perhaps older, even, than the song itself!

As to the historical basis of the events of the song, there were many travelling people in 16th and 17th century Scotland who went by the name of Johnnie Faa (or Faw, or Fall). The earliest known of these, Johnne Faw, had been granted remarkable royal privileges by King James V in 1540 and dubbed “lord and erle of Litill Egipt”. It’s thought that from then, other travelling people would opportunistically adopted the name in order to avoid falling foul of the law. However any protection offered by the name was short-lived as the King’s privileges were withdrawn and, in the years that followed, the laws that discriminated against travelling people were extended and stiffened. Between 1611 and 1624, three separate men, all known as Johnnie Faa were to die at the gallows. In one of these cases one of the members of the Privy Council responsible for handing down the death sentence was the 5th Earl of Cassillis!

As is the case with all the best old stories, history can neither confirm nor entirely refute the tradition — and the Kennedy family may even have embraced the legend themselves following Burns’s canonisation as Scotland’s national bard.

Culzean painted by Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840) – in the days when smugglers plied the Carrick coast.

Culzean painted by Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840) – in the days when smugglers plied the Carrick coast.Images of old tunes appear courtesy of hms.scot and University of Glasgow Library.